Many of you do not know but over the past year, I've gone back to studies. I'm in the second year of a PhD (English Studies/Creative Writing) at Durham University in the UK. (Please hold your congratulations until I've actually finished doing this; send good luck and fortitude instead). It has been over two decades since I was a scholar and I was rather nervous about my own aptitude viz academic reading and writing. I am mainly a practitioner and a background in journalism teaches you something about research but it does not involve quite the same degree of immersion in one topic and any analysis you offer doesn't have to be supported/evidenced to the same extent. Doctoral research, even if you do it via artistic practice, is different. I've made it past the one year mark, so I thought I should let more people know. Some of you have been reaching out, inviting me to places and events now that things are opening up again after the Covid-19 situation. Or asking me to read and review or blurb books and I have not been able to do much because there is SO MUCH reading to do towards my own research.

In case you're wondering, I'm looking at the figure of the witch in contemporary South Asian fiction, and starting to feel like I do know something about it. In case you're also wondering, unlike an MFA, a creative writing PhD is not geared towards the production of a novel or a collection of poetry. One submits some creative work but it is research based, AND a critical thesis that contextualizes the research, provides a theoretical framework for it either within the field or across disciplines where necessary.

When I started to apply, someone had asked me: why do you need to do this? Need is the wrong word, of course. I want to do this. I've just never been able to afford it before. I have applied and been accepted twice before, at a Masters' programme in the UK when I was in my early 20s and then an MFA programme in the USA in my late 20s. But there was no money, not even enough money to defer admission and to reapply the next year for more scholarships, or to take a year off just to build a stronger application. I was determined not to ask anyone else, not even my own family, for that much money. So it took me much longer. It was during the pandemic that I finally began to clear my head and think about how far I've come and how much further I want to go, and what kinds of things I want to work on in the future.

A PhD is very hard work; it is not the same as starting a new literary project. There are days when I am physically exhausted from trying to understand yet another chapter or theory. However, if you want to go back to studies after a long break, I recommend you do so. Here, I am relieved to notice some grey heads and harried parents of teenagers at conferences and seminars. It is good to be free of that nonsense about 'Why are they still in university?' Education is for everyone and research especially (in my view) gets more interesting when you have some experience of the world. I feel better prepared to undertake my research now, with more confidence and curiosity than when I was in my 20s.

Tuesday, November 29, 2022

Friday, November 11, 2022

On Reading Sara Suleri's Meatless Days

What a thing it is to discover a good book decades after it has been written! I wonder why nobody told me to read Sara Suleri's Meatless Days before? There were so many South Asian, especially diasporic, novels discussed over the last twenty years but not once did I hear anyone say: if you just want to look at good writing -- experimental writing that defies assumptions of genre -- read Meatless Days. I am both moved and startled by it. Some of the sentences are of such a sensory quality that I find myself wanting to lick them off the page (I don't actually do that. I don't! Really, I don't!). The language is a felt one, communicating itself with such a sharp metaphorical edge at times, it is like a new flavour on the tongue; at other times, it engages my literary senses with a sweet viscosity.

On the other hand, I am glad that I did not read this book before I wrote my own Bread, Cement, Cactus for it may have influenced the style in which I attempted a memoir of belonging and home, and this would not have been a good thing. Suleri's book is, in its own way, a sort of reaching for home but I needed to write a very different kind of memoir. I needed to grasp home as a sociocultural and political concept rather than reach for it within my own heart.

Suleri wrote a memoir that does something other than giving us a story about a well-known person, that opening of social doors and letting secrets spill, or even an account of living in a particular place at a particular time, taking us on a journey with a character with all their trials. Instead, it tells us what an emotional life is constructed of, using emotional tools that must be fashioned with one's own hands and memories so that, in the end, we are left with the author's heart rather than an account of her days. It is a memoir of love, not an account of relationships but a cloudy distillate in memory.

I did get tripped up sometimes by the language of the academic that sits within the writer. She uses 'discourse' instead of conversation or talk but she uses the term precisely, letting it describe an environment. A person can turn into a discourse, within himself or for the people in his life, or on account of a particular way of living and writing, seeing and refusing to see. She uses the word casually, but conscious of its possibilities. It is a pity she didn't write more fiction; I would have liked to see what she did with it but perhaps it is just as well. I think I will look out for her other book, also a personal narrative by the sound of it.

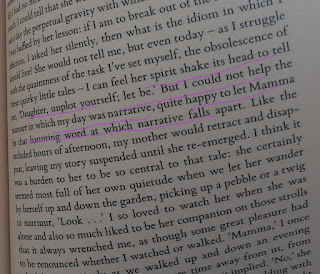

In the meantime, I leave you with these brief bits, where she talks about 'sentences' and her relationship with them from her earliest days, and the way she recalls her late mother and elder sister.

On the other hand, I am glad that I did not read this book before I wrote my own Bread, Cement, Cactus for it may have influenced the style in which I attempted a memoir of belonging and home, and this would not have been a good thing. Suleri's book is, in its own way, a sort of reaching for home but I needed to write a very different kind of memoir. I needed to grasp home as a sociocultural and political concept rather than reach for it within my own heart.

Suleri wrote a memoir that does something other than giving us a story about a well-known person, that opening of social doors and letting secrets spill, or even an account of living in a particular place at a particular time, taking us on a journey with a character with all their trials. Instead, it tells us what an emotional life is constructed of, using emotional tools that must be fashioned with one's own hands and memories so that, in the end, we are left with the author's heart rather than an account of her days. It is a memoir of love, not an account of relationships but a cloudy distillate in memory.

I did get tripped up sometimes by the language of the academic that sits within the writer. She uses 'discourse' instead of conversation or talk but she uses the term precisely, letting it describe an environment. A person can turn into a discourse, within himself or for the people in his life, or on account of a particular way of living and writing, seeing and refusing to see. She uses the word casually, but conscious of its possibilities. It is a pity she didn't write more fiction; I would have liked to see what she did with it but perhaps it is just as well. I think I will look out for her other book, also a personal narrative by the sound of it.

In the meantime, I leave you with these brief bits, where she talks about 'sentences' and her relationship with them from her earliest days, and the way she recalls her late mother and elder sister.

Monday, November 07, 2022

After Sappho: a review

Spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the story introduces the reader to women who rejected factory and homestead and immersed themselves in classical poetry, plays, novels, pamphlets, paintings, dancing. The performers among them responded to contemporary works such as Ibsen’s A Doll’s House and Oscar Wilde’s Salome, while others such as Colette, Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf wrote their own novels and plays.

Living in France, Italy, Greece or England, many of these women had privileges associated with a middle- or upper-class background. Apart from one named working-class character—Berthe Cleryrergue, a housekeeper who wrote a memoir about the years she spent working for Natalie Barney—most characters appear to be women of some means. They are able to host and attend salons in Paris or travel across the continent, to Lesbos or Capri. They refuse to slip easily into the robes of obedient wives and mothers, and if they cannot flee, they subvert the norms of heterosexual marriage.

Yet, this is not a novel about privilege though it does draw attention to the nature of privilege through the prism of gender. After all, what privilege does a businessman’s daughter have if her father simply hands her over to her rapist? What does privilege mean if you have no say in the workings of the nation, no matter how educated you are or how ignorant the men who rule against you?

Living in France, Italy, Greece or England, many of these women had privileges associated with a middle- or upper-class background. Apart from one named working-class character—Berthe Cleryrergue, a housekeeper who wrote a memoir about the years she spent working for Natalie Barney—most characters appear to be women of some means. They are able to host and attend salons in Paris or travel across the continent, to Lesbos or Capri. They refuse to slip easily into the robes of obedient wives and mothers, and if they cannot flee, they subvert the norms of heterosexual marriage.

Yet, this is not a novel about privilege though it does draw attention to the nature of privilege through the prism of gender. After all, what privilege does a businessman’s daughter have if her father simply hands her over to her rapist? What does privilege mean if you have no say in the workings of the nation, no matter how educated you are or how ignorant the men who rule against you?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)