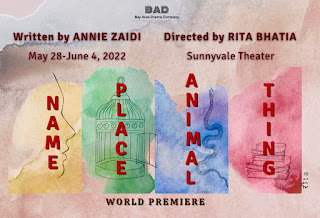

I was interviewed by Chintan Girish Modi this week about my new book. One question in particular led me to think deeper around a topic that I had been debating internally for a while, so I put down my thoughts at some length.

Q. What are some of the ethical questions that you grapple with while writing about people whose lives are available to you through observation but far removed from your own experience? For instance, people who sleep on pavements and under bridges.

Annie - I have been reading around the question of cultural representation, ‘voice’ and debates about who should write what. I run the risk of writing an essay in response to your question, but this is as good a time as any to put down some reflections and fears.

The first aspect of this question is: Should one write of what/who one sees, or should one only write about what one has personally experienced? I have to say that I disagree with the notion that one should only write what one experiences. People are told ‘write what you know’, especially when they are just starting to write, because they may not have an instinctive, immediate capacity for vivid or plausible description based only on imagination. But if we all only wrote what we have personally experienced, we’d only churn out diaries and memoirs. Where does that leave fiction? Science fiction, fantasy and historical fiction would be absolutely impossible under such conditions.

Besides, the point of literature, especially fiction, is to transpose. The writer transposes herself by building up characters in a world that may not be based on lived experience. Even if it is ‘real’, the writer could have experienced only part of it. If it is conjured, that world is unexperience-able. If it is a combination of real and conjured, the writer herself neither knows nor does not-know. She can only try to capture feelings the way one tries to capture images and memories.

Even within a narrow range of experience, within the same caste, class, religion, gender, it is impossible to represent or experience another life. You may think you ‘know’, but do you? My grandmother’s life was very different from mine though we have the same gender, class/caste background. I observed her, but her experience was not mine. Should I not write about her? I believe I should. Even if she has told her own story in her words, I should still try and make sense of her as a character from my perspective, maybe even try to make sense of my own self as a character seen from her lens.

The second part of the question is about assumptions about knowing. Do we ‘know’? To answer that, we must dip into philosophy, spirituality, neuroscience, and this is not a suitable venue for such expansions, nor am I a scholar of such breadth. To a writer, the more relevant question is: Can we know through reading and writing? Can we know each other’s hearts? Can we at least try? And my response is to try.

The third part of your question is about the person observed. We all observe people whose lives are far removed from our own. There’s little question of an ethical dilemma if the gaze is reversed, say, if a homeless man were to write about a woman riding in a bus one hot afternoon. So, this question is not about who observes; it is about who writes. In theory, anyone. In practice, not everyone.

So, I disagree with the framing of the debate though I agree that it is important to discuss who is allowed what in our society. The shape of the argument must clarify its true ethical intent: everyone deserves a voice. Everyone deserves to be able to read and write. For this, we have to argue that everyone deserves housing and cultural materials. Food, clothing, shelter, but also books, performances and internet access. In countries that do have such a vision, there are public libraries equipped with computers; people can use them for free. There are high-quality, free performances in public spaces like parks or town squares.

The fourth part is the core of the debate: equity. The ethics question arises not because of who is writing but because of who is not writing, not getting published.

I’ve considered this debate by imagining myself in the position of one who has limited cultural access. If I become part of a very tiny minority in another location, and I can’t find a publisher for my work, or don’t have the time to write fiction, or can’t find a publisher that publishes in my language, do I want others to not write about women like me? My answer is: if they can write with empathy and insight, then they should. However, I also want an environment conducive to me writing in my own language.

I also imagine the alternative: what if writers actually stopped describing lives outside of their experience? Nirala wrote about Kulli Bhat. Kulli Bhat should have been able to write about Nirala too. Should Nirala have refused to describe what he was seeing and hearing, and limited himself to writing about his own family? What would be gained from that moment in time, in literature, in our country’s consciousness, not being written? Kamala Markandeya wrote Nectar in a Sieve, about a farmer couple and their distress. The farmer should have written too. But would we be better served by Markandeya writing only about upper or middle class, English-speaking women?

There is obviously a vast difference between stories based on observation and what emerges from lived experience. This is a difference between Markandeya or even Mahasweta Devi’s work, and that of Manoranjan Byapari or Baby Halder. But I don’t think it is a good idea to create rules about who should write about what. It is bound to boomerang. If we say that white people can’t write about black or brown lives, can we argue that black and brown people do have the right to write about white people or their motivations? Or are we only allowed to write from the perspective of a victimized/colonized person? Such rules are easily hijacked by those who are politically and socially powerful, and used against those who are trying to right the balance of power. There is a danger of writers who write about class or caste divisions being silenced on the grounds that they don’t really know what they’re talking about, because they cannot possibly have experienced both (or all) sides of the divide.

In an oral literary culture, cultural equity is easier to achieve. Ali Khan Mahmudabad, in his book Poetry of Belonging, writes about mushairas where unlettered, working class poets participated alongside upper and middle class poets. Publishing and, even more significantly, distribution equity is much harder to achieve. So we must advocate for publishing those who want to write but can’t access literary organizations. We must ask for free libraries too.

When we strike a blow for equality, we must be aware of how the blow lands, and whether it has the desired impact. Is the blow landing on the shoulders of writers of fiction, instead of shaking up governments and leading to policy changes? We have no comprehensive data about the income/caste/gender profile of writers in India. We still need permission from the censors to enact a play, permission from the police to perform on the streets. But I notice that the more inequality increases in the world, the more people focus their critiques on artists and their individual choices instead of turning on structural inequity, patriarchy and state policy.

What power does a writer have, after all, except powers of observation, comprehension and empathy, and a certain felicity with language? You write about what you see or know, about what matters to you, what moves you, what you feel is important. That is the core of a writer’s ethic. Or, my ethic anyway.

The full interview is available here:

https://www.news9live.com/art-culture/annie-zaidi-large-cities-impress-upon-us-a-painful-economy-of-leisure-and-socialisation-151690