Have often thought about sanity, the people we consider sane, and the forces that push some of us beyond - into that other place in the head. Some of those thoughts are compressed here, in another story for The Small Picture in Mint.

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

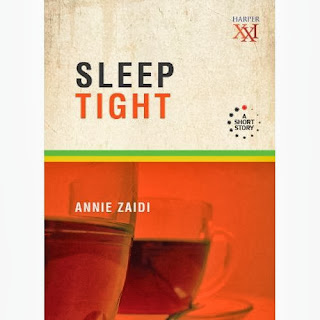

A new single read

I have a new short story out. It is the story of a man who has almost nothing to live for, except the fact that a woman called Noora still lives.

Available only online so far. Rs 21 for the e-single (as single short stories are sold now for readers who use, erm, readers). You can get it here.

Available only online so far. Rs 21 for the e-single (as single short stories are sold now for readers who use, erm, readers). You can get it here.

Monday, September 23, 2013

On testing the way the wind blows

A few days ago, former Deputy Chief Minister of Bihar Sushil Kumar Modi reportedly tweeted: “Advaniji has failed to gauge the public mood”. He said LK Advani should have declared Narendra Modi as the BJP’s Prime Ministerial candidate for the coming general election.

It is no secret that 'Advaniji' had held prime ministerial hopes for over twenty years, and now it’s too late. His brand of politics has been sharpened to rapier point by younger men. So he has had to finally endorse Narendra Modi at public rallies.

Let us, for a moment, forget who is less suitable between the two men. Instead, let’s examine Sushil Modi’s lobbing of unsolicited 140-character chunks of advice at 'Advaniji'.

On the face of it, this sounds like good advice. In a democracy, elections are a reflection of public will. If people are discontent and thirsting for change, they’ll let you know. And it is true that a politician ceases to be significant if he disregards the electorate. A good politician is aware of, and sensitive to, the public mood.

But the problem with Sushil Modi’s advice is that it reduces leadership to mere politicking. It takes away from a politician the right to be a leader. It expects a politician to bow to ideas that please a sufficient number of people in order to win an election, and trample upon truth and Constitutional rights lest he/she is punished with powerlessness. In effect, it reduces a leader to an unthinking, spineless slave of the majority view (or whatever passes for the majority).

I don’t know if Advani’s misgivings about Narendra Modi’s leadership are moral. I doubt this. But I also think that our leaders owe us a personal moral compass. We need them to stand up for their own beliefs rather than just kowtow to the ‘public mood’.

Where have all our true leaders gone? This is our constant complaint. We imagine governance as a ship lost at sea. We think of politicians as wicked pirates (except they’re not fighting fit). But we forget what goes into the making of true leaders.

Think of the men and women whose names went into history textbooks for steering modern India through her independence struggle. MK Gandhi survived (and ultimately fell to) assassination attempts, not by the British but by Indians, who did not like his ideas on caste or religion. In nineteenth century India, notions of pollution-purity were the norm. Most leaders were upper caste and most of the country was illiterate. If public approval was all they sought, they would never have endorsed universal suffrage.

Inter-communal marriage was very rare in the 1920s. But Aruna Asaf Ali chose to risk public antagonism for the sake of her own values. Leaders like C Rajagopalachari risked political exile when they walked away from the party they helped to build.

It is not the job of a leader to be the public. A leader represents us, yes, but he/she must work for more than public approval. The job description includes upholding the Constitution; enforcing laws; making laws for a future; rejecting what is unworthy in our present; making justice a broader, more humane reality.

Sometimes this means being in conflict with the majority. If 51% of India wanted that 49% be turned into landless labourers with no access to drinking water, should a leader care about ‘public mood’? What if it’s 65% and 35%? What if it’s 78% and 22%? When does it become right to allow ‘public mood’ to dictate political decisions?

A good leader is someone willing to work to reshape popular ideas, redirect public energy and risk public displeasure. As far as gauging the public mood goes, any politician can do that.

[A version of this was published in DNA]

Friday, September 20, 2013

More than a database of grief

There is a stockpile of shared grief within each of us. It threatens to render the taste of life ash on our tongues. Each riot, every famine, each genocidal attack, racist attack, each horrific moment of hate. The maps of the world, of our place in the world, of our identity are marked by pain. And we go on. That is the thing. Without knowing why we suffered, or how to learn to trust again, we go on.

Survival is an instinct but our individual and social can matter only if we let go of past pain and find fresh reserves of trust, veering more and more and more towards the side of justice. And trying not privilege the grief of one race, one religion, or one gender over the other.

'Ground Zero', was written for The Small Picture which appears in Mint, beautifully illustrated by Prabha Mallya.

Survival is an instinct but our individual and social can matter only if we let go of past pain and find fresh reserves of trust, veering more and more and more towards the side of justice. And trying not privilege the grief of one race, one religion, or one gender over the other.

'Ground Zero', was written for The Small Picture which appears in Mint, beautifully illustrated by Prabha Mallya.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Saying it with the body

There is something about a rally or protest

that announces itself even when it is not announced audibly. Like girls walking

down the street in rows two or three thick, a fantastic array of colour and

style. You stop to look. When you see the first fifteen or twenty, you wonder

if it is for a festival. When you see fifty, and none of them conforming to any

particular dress code, you know it is a rally.

You see that some of the girls are wearing

clothes that would be considered outrageous on the street even in a foreign

country where skirts, leggings and shorts are the norm. Then you see a girl

wearing nothing but a thong (or a g-string; it is difficult to tell from a

distance). Another whose breasts are bare except for her nipples. A few brave

men too.

Only after hundreds have walked past, you

see the placards. It is a Slut Walk in Melbourne. But you no longer need

placards to tell you what this is about. Girls wearing next to nothing march

beside girls in frilly frocks down to their ankles – they said what they had to

say with their bodies. Mainly, that bodies are what they are. Clothes are what

they are. What they are not is an excuse for violence.

Witnessing this Slut Walk reminded me that

flesh has its own power. Not just the power of sex or seduction, but the power

of truth. To bare oneself as a statement of fact: “This is what a woman looks

like. So?” To wear their womanhood on the streets was inconvenient (for one, it

was just too cold and windy) but it is not a call for violence.

[Photo courtesy Nicolas Low]

[Photo courtesy Nicolas Low]

Watching those women put to rest certain

doubts for me, personally. In India, there had been several debates about Slut

Walk – its viability or lack of cultural sensitivity. Did it make sense in a

nation where little girls are raped everyday, and where women are often raped

in front of their families?

Finally, I think it does make sense.

Because people all over the world are frightened of the power of the human

body. They are also afraid of those who veer from the norm, for there is power

in both – conformity and non-conformity. And all human societies are based on

power struggles.

Since it is easier to gain power through

attacking a woman walking down the street than to lead an army, or build a

fortress, or even just to fight a court case against neighbours, that is precisely

what happens. That is why, in India, a bunch of village 'elders' can order an

eight-year-old to marry into the family of her rapist. Because it is easier to

impose further punishment upon her and her family than to punish the rapist, or

risk annoying his family.

And that is why a bunch of criminal men can

attack a group of women in Mangalore, because they are at a resort. Because it

is easy to do so. Because they can argue that women going to resorts of their

own volition, for whatever purpose, is akin to prostitution. Because they claim

to speak for India when they say such women deserve to be hurt. They do this

because the rest of us are too frightened of the body, of its truth, to

challenge them.

We find ourselves shamed by our body, again

and again, because we fail to speak up for it. But watching those women in

Melbourne, I was finally convinced that the only way to reclaim this power of

the body is to stop denying it.

First published here

First published here

Monday, September 09, 2013

Legislating filial love

A few months ago, I read about a law that makes it mandatory for Chinese citizens to visit elderly parents.

My immediate thought was that this is an unimaginative, if not un-implementable, law. My next thought was — have matters really come to a pass that the state must legislate family relationships?

Then I remembered that India had also passed the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, in 2007. It asks children to maintain a ‘normal’ life for parents, but didn’t mention emotional needs. In China, parents have been suing children for neglect. Some reports mentioned ‘ill-treatment and abandonment’, others refer to ‘filial piety’. So, the government is saying that their ‘daily, financial and spiritual needs’ should be met by grown children. In theory, it’s a reasonable expectation — children should visit aging parents. They should call, and Skype, and express affection. But if they do not want to, can a law make them? Even in India, few parents have the heart — or the physical energy — to drag negligent offspring to court.

It is impossible to seek affection legally. And I am not sure it is a good idea to force young (or middle-aged) people to pretend at love. Besides, if affection is being made a legal construct, perhaps lawmakers should also consider the truth of family life. Not every parent considers the emotional needs of a child. Many parents assume they’ve done their duty if they just cater to physical needs, and make him/her employable. It is foolish and unjust to expect that all children will grow up to lavish affection upon all parents.

Indians are like the Chinese when it comes to family expectations. In one report, a Chinese woman was quoted as saying that in their culture, parents invest in children as a support for their old age. I can imagine lots of Indian parents expressing similar views. But I cannot imagine that children like being treated as some sort of emotional-social security plan.

In the Chinese context, everyone is pointing fingers at the one-child norm. It is estimated that by 2050, every third Chinese will be a senior citizen. But the problem of more and more old people and fewer young people is a global one.

There was another report from Japan, where it is estimated that by 2020, the market for adult diapers will be larger than that for baby diapers.

India already has 100 million senior citizens and by 2050, every fifth Indian will be old. Not only do we not have universal pension coverage, most pensions are too small to allow an aging, ill person to survive independently.

Most Indians cannot afford the basics — clean water, safe housing, a varied diet, decent education — even for small children. Steady jobs are hard to come by.

‘Parents’ emotional needs’ are low on the list of priorities. And though that is not a justification for the abuse or neglect of the elderly, we must not forget that there is also an emotional cost for children — to know that there are ways to keep parents alive and healthy, but not the means.

So, what should children and parents and the government do? For one, we can start investing in the future instead of waiting to reach a point of crisis. Senior citizens need an upgrade of skills in middle age. They need access to legal aid to ensure their property is not taken away. They need regular events and public spaces where they can meet other people of all ages, and they need community-supported retirement homes and hospices. Even if those are not ideal choices, the choice must exist.

First published here

My immediate thought was that this is an unimaginative, if not un-implementable, law. My next thought was — have matters really come to a pass that the state must legislate family relationships?

Then I remembered that India had also passed the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, in 2007. It asks children to maintain a ‘normal’ life for parents, but didn’t mention emotional needs. In China, parents have been suing children for neglect. Some reports mentioned ‘ill-treatment and abandonment’, others refer to ‘filial piety’. So, the government is saying that their ‘daily, financial and spiritual needs’ should be met by grown children. In theory, it’s a reasonable expectation — children should visit aging parents. They should call, and Skype, and express affection. But if they do not want to, can a law make them? Even in India, few parents have the heart — or the physical energy — to drag negligent offspring to court.

It is impossible to seek affection legally. And I am not sure it is a good idea to force young (or middle-aged) people to pretend at love. Besides, if affection is being made a legal construct, perhaps lawmakers should also consider the truth of family life. Not every parent considers the emotional needs of a child. Many parents assume they’ve done their duty if they just cater to physical needs, and make him/her employable. It is foolish and unjust to expect that all children will grow up to lavish affection upon all parents.

Indians are like the Chinese when it comes to family expectations. In one report, a Chinese woman was quoted as saying that in their culture, parents invest in children as a support for their old age. I can imagine lots of Indian parents expressing similar views. But I cannot imagine that children like being treated as some sort of emotional-social security plan.

In the Chinese context, everyone is pointing fingers at the one-child norm. It is estimated that by 2050, every third Chinese will be a senior citizen. But the problem of more and more old people and fewer young people is a global one.

There was another report from Japan, where it is estimated that by 2020, the market for adult diapers will be larger than that for baby diapers.

India already has 100 million senior citizens and by 2050, every fifth Indian will be old. Not only do we not have universal pension coverage, most pensions are too small to allow an aging, ill person to survive independently.

Most Indians cannot afford the basics — clean water, safe housing, a varied diet, decent education — even for small children. Steady jobs are hard to come by.

‘Parents’ emotional needs’ are low on the list of priorities. And though that is not a justification for the abuse or neglect of the elderly, we must not forget that there is also an emotional cost for children — to know that there are ways to keep parents alive and healthy, but not the means.

So, what should children and parents and the government do? For one, we can start investing in the future instead of waiting to reach a point of crisis. Senior citizens need an upgrade of skills in middle age. They need access to legal aid to ensure their property is not taken away. They need regular events and public spaces where they can meet other people of all ages, and they need community-supported retirement homes and hospices. Even if those are not ideal choices, the choice must exist.

First published here

Wednesday, September 04, 2013

Some thoughts on a 49% (or 4.9%) view of democracy

Last week, I’d mentioned the Majority and its role in keeping a democracy healthy.

Our rulers are decided by a majority vote. It could be just 51%. This is frustrating for the 49% who voted against. But still, elections are a much better way of deciding power struggles than building armies and turning each others’ homes into crematoria.

What, then, happens to the 49%?

If your representative loses, the assumption is that your values, your financial interests, your ethnic group have a smaller chance of flourishing.

In a country like ours, an electoral minority is often confused with a caste or a religion, but it could also be a tribe, a region. It could be any group that will not be able to influence decisions on the strength of its numbers.

But if you keep feeling neglected or exploited, you begin to look for ways to create a fresh electorate, one where you are not such a minority. Hence, new states. Like Telangana. Or Gorkhaland. Or Uttarakhand. One of the reasons people who live in remote hill villages demanded a separate state to be carved out of Uttar Pradesh was that they were never heard in faraway Lucknow.

Sometimes, people find that a geographic separation has not worked out. So, they make demands that are directly linked to an ethnic group. In Chhattisgarh, for instance, there were reports from a World Adivasi Day function held recently, that many adivasis felt they’d be better off with an adivasi Chief Minister. Yet, in a state where adivasis are not a numeric majority, this is difficult.

As for minorities, well, there’s a majority even within the minority. This group always finds itself trampled upon by those who claim to represent them. You might survive (depending on your wealth and education) but you find yourself constantly pushed into the minority corner, unable to participate in law-making.

Eventually, you’re going to ask what these words should mean to somebody like you -- nation, independence, culture, law.

Consider linguistic minorities. Hindi became the national language because it was the single-largest language in India. Rajasthani, Bhojpuri, even Bhoti-speaking people found themselves swept under the carpet of ‘Hindi’.

Governments correspond with barely literate citizens in a language that even I am flummoxed by although I’m firmly, fluently Hindi-speaking. Those who do not speak the Hindi that a ‘Hindi-speaking’ state uses are not even acknowledged, forget being included in consultations with officials.

Or, consider how India got saddled with marriage laws that were followed only by upper-caste Hindus. Or why there is so little room for the wisdom of communities who lived quite happily (am assuming a lot here, but happy in the marital context being construed to mean a system that is tolerated and passed down over generations) through different marital practices, including polyandry.

Songs, sexual freedom, history, progress - everything can be held hostage under this heavy blanket of ‘majority’ or ‘mainstream’. Hundreds of millions among us must abide by someone else’s morals, someone else’s ideas about prosperity, someone’s version of the truth, because the minority view will be crushed. And those who do the crushing will escape, unpunished.

The majority or mainstream turn arrogant if they stay powerful for too long. They speak in the name of ‘all’, take liberties with common resources, or hurt others. This is possible because their representatives protect them, in lieu of electoral fealty.

Does this hurt the nation?

In a country like ours, an electoral minority is often confused with a caste or a religion, but it could also be a tribe, a region. It could be any group that will not be able to influence decisions on the strength of its numbers.

But if you keep feeling neglected or exploited, you begin to look for ways to create a fresh electorate, one where you are not such a minority. Hence, new states. Like Telangana. Or Gorkhaland. Or Uttarakhand. One of the reasons people who live in remote hill villages demanded a separate state to be carved out of Uttar Pradesh was that they were never heard in faraway Lucknow.

Sometimes, people find that a geographic separation has not worked out. So, they make demands that are directly linked to an ethnic group. In Chhattisgarh, for instance, there were reports from a World Adivasi Day function held recently, that many adivasis felt they’d be better off with an adivasi Chief Minister. Yet, in a state where adivasis are not a numeric majority, this is difficult.

As for minorities, well, there’s a majority even within the minority. This group always finds itself trampled upon by those who claim to represent them. You might survive (depending on your wealth and education) but you find yourself constantly pushed into the minority corner, unable to participate in law-making.

Eventually, you’re going to ask what these words should mean to somebody like you -- nation, independence, culture, law.

Consider linguistic minorities. Hindi became the national language because it was the single-largest language in India. Rajasthani, Bhojpuri, even Bhoti-speaking people found themselves swept under the carpet of ‘Hindi’.

Governments correspond with barely literate citizens in a language that even I am flummoxed by although I’m firmly, fluently Hindi-speaking. Those who do not speak the Hindi that a ‘Hindi-speaking’ state uses are not even acknowledged, forget being included in consultations with officials.

Or, consider how India got saddled with marriage laws that were followed only by upper-caste Hindus. Or why there is so little room for the wisdom of communities who lived quite happily (am assuming a lot here, but happy in the marital context being construed to mean a system that is tolerated and passed down over generations) through different marital practices, including polyandry.

Songs, sexual freedom, history, progress - everything can be held hostage under this heavy blanket of ‘majority’ or ‘mainstream’. Hundreds of millions among us must abide by someone else’s morals, someone else’s ideas about prosperity, someone’s version of the truth, because the minority view will be crushed. And those who do the crushing will escape, unpunished.

The majority or mainstream turn arrogant if they stay powerful for too long. They speak in the name of ‘all’, take liberties with common resources, or hurt others. This is possible because their representatives protect them, in lieu of electoral fealty.

Does this hurt the nation?

Well, that depends on who gets to define ‘nation’. If the idea of India belongs to each citizen in equal measure, then yes, it hurts. To be a free citizen is to have the freedom to live by your values, legally practice your culture, but not be allowed to impose this on anyone else, not even on your family.

First published here.

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Do we really want justice?

If we were to make a list of the most urgent problems in India, I can safely bet that ‘politicians’ would be on everyone’s list. They might even top the list. They are on my list too.

Corruption is endemic. We are defeated by it in every way imaginable. And while politicians or bureaucrats are definitely not the only ones guilty, it is actually important to focus on political leaders. Not just because India is represented by politicians, but also because they reflect our own aspirations. They are our face in the mirror — a face bloated out of all recognition but still, there’s no denying that the politician’s face represents the majority.

This is key: Representation. It is why ministers are called upon to resign when something goes very wrong. Say, a railway accident happened and the fault lay with faulty equipment or over-worked drivers. The rail minister may offer to resign, as a way of saying: ‘I am in charge and a systemic failure is my failure’. If it is clear that another group of people are responsible, they must be punished instead.

If we fail to punish politicians in a democratic way, our democracy sours. When we fail to question politicians about why they act in ways that are contrary to the electorate’s values and aspirations, we are building a society without accountability.

If we do this over several years, then there is little doubt that this is what we actually want for ourselves — we do not want to be punished for corruption; we do not want to be held accountable at our jobs; we recognise that we ourselves would divide people on the basis of caste and religion because it suits us to do. We would inflict violence upon other citizens when we think we can get away with it, and that is why we do not really cry out against politicians. Because far too many of us are guilty of the same acts of commission and omission.

This is part of the reason why I was very pleased to hear that Sajjad Kichloo, Minister of State (Home) had resigned in the wake of the violence that broke out recently in Kishtwar, Jammu and Kashmir. Kichloo may or may not have ‘felt’ responsible. After all, the army was called out in a few hours, a curfew was imposed, and hundreds of people were not killed.

Still, there were allegations that the state police did not do its job. And so, the minister shouldered his responsibility and the J&K government promptly ordered an inquiry. Therefore, Chief Minister Omar Abdullah has every right to ask — what about Gujarat 2002?

There was evident mismanagement at least, if not a deliberate pogrom. One can ask the same question about Delhi, 1984. In fact, one should ask and one is asking. What about Bombay 1992? What about 1993? Who resigned? How long did it take for someone in power to take responsibility?

Surely, someone should have resigned. Surely, a good leader does not promote and reward trouble-makers? Surely, such leaders don’t deserve to be re-elected?

But if we continue to insist that this is good leadership, if we continue to elect such men and women to office, then that is a way of saying that we are electing what is us. At least, the majority of us. That the twisted face in the mirror does not just wear our face like a mask. That face is our face. That soul is our soul, and it does not crave justice.

Which leaves us with this awful question — if not justice, then what do we actually crave?

Corruption is endemic. We are defeated by it in every way imaginable. And while politicians or bureaucrats are definitely not the only ones guilty, it is actually important to focus on political leaders. Not just because India is represented by politicians, but also because they reflect our own aspirations. They are our face in the mirror — a face bloated out of all recognition but still, there’s no denying that the politician’s face represents the majority.

This is key: Representation. It is why ministers are called upon to resign when something goes very wrong. Say, a railway accident happened and the fault lay with faulty equipment or over-worked drivers. The rail minister may offer to resign, as a way of saying: ‘I am in charge and a systemic failure is my failure’. If it is clear that another group of people are responsible, they must be punished instead.

If we fail to punish politicians in a democratic way, our democracy sours. When we fail to question politicians about why they act in ways that are contrary to the electorate’s values and aspirations, we are building a society without accountability.

If we do this over several years, then there is little doubt that this is what we actually want for ourselves — we do not want to be punished for corruption; we do not want to be held accountable at our jobs; we recognise that we ourselves would divide people on the basis of caste and religion because it suits us to do. We would inflict violence upon other citizens when we think we can get away with it, and that is why we do not really cry out against politicians. Because far too many of us are guilty of the same acts of commission and omission.

This is part of the reason why I was very pleased to hear that Sajjad Kichloo, Minister of State (Home) had resigned in the wake of the violence that broke out recently in Kishtwar, Jammu and Kashmir. Kichloo may or may not have ‘felt’ responsible. After all, the army was called out in a few hours, a curfew was imposed, and hundreds of people were not killed.

Still, there were allegations that the state police did not do its job. And so, the minister shouldered his responsibility and the J&K government promptly ordered an inquiry. Therefore, Chief Minister Omar Abdullah has every right to ask — what about Gujarat 2002?

There was evident mismanagement at least, if not a deliberate pogrom. One can ask the same question about Delhi, 1984. In fact, one should ask and one is asking. What about Bombay 1992? What about 1993? Who resigned? How long did it take for someone in power to take responsibility?

Surely, someone should have resigned. Surely, a good leader does not promote and reward trouble-makers? Surely, such leaders don’t deserve to be re-elected?

But if we continue to insist that this is good leadership, if we continue to elect such men and women to office, then that is a way of saying that we are electing what is us. At least, the majority of us. That the twisted face in the mirror does not just wear our face like a mask. That face is our face. That soul is our soul, and it does not crave justice.

Which leaves us with this awful question — if not justice, then what do we actually crave?

First published here

Monday, August 19, 2013

Getting out of the cage

By now, you would have read some reams about what stops our great nation from being truly free etcetera.

I’ve been reading a lot of books recently that were written before 1947 or set in the ‘Colonial’ era. These books have been breaking down the neat constructs of schoolbook history. We’d been given to understand that the British sailed east (like the Portuguese and French), saw that India was rich, began to wage battles against ‘our’ kings and began to rule India.

But the truth was slightly different. For starters, there was no ‘us’. There were hundreds of kingdoms, all part of a power hierarchy. A kingdom could be ‘sovereign’ but it might have to pay tribute to a bigger, more powerful kingdom. That was the only way to stay ‘independent’. It was the only way a king or queen could stay on the throne. If kings or queens were devoted to citizen welfare, they would also sign peace treaties to save people from violence and total economic ruin in the course of war. Our ‘foreign invaders’ could be Bhutanese (from Assam’s perspective), Maratha (from Bhopal’s perspective), or Tibetan (from Spiti’s perspective).

But Britain gained in power to the extent that almost all kingdoms – despite racial and cultural differences – suffered. Taxes were heavy; wealth was leaving the subcontinent. Now, there was a common enemy, racially different and blatantly discriminatory. So enough people – even the rich – could say: ‘Quit India’.

It took a long time but Britain did quit India, politically at least. And ‘India’ was born. But that didn’t mean we stopped trying to enslave other citizens.

There was a recent news article about a domestic worker from Jharkhand, a teenaged girl, who was beaten and starved for three days by her employer. Does this not sound like a slavery? The teenager survived but imagine her situation – she doesn’t speak any of the three main languages that most neighbours would have spoken; she had no money and circumstances at home were probably desperate enough for her to be sent to Mumbai in the first place.

Another report from Kanpur. A husband asks his pregnant wife to undergo a sex-determination test for the foetus. She refuses. He pours acid on her private parts. Now think of the wife’s situation – perhaps she has no money or property; if she had walked out on her husband before, she would face the risk of attacks from other men. The police and legal system being what it is in our country, she couldn’t have hoped for timely intervention in any case. Does this not sound like a slavery-enabling system?

It has become fashionable to dismiss M.K. Gandhi and his methods of non-violence, non-cooperation, and self-reflection. But there is a reason Gandhi chose these tools in the struggle for freedom. What was being done to us by imperialist forces was violence. Indians were not necessarily being locked up in a cage, or whipped. Those might be our mental images of slavery. Our main shackles were economic and psychological.

We could not make decisions for ourselves, nor controlled natural resources. If we tried to, we confronted physical violence. Which is exactly what is happening to hundreds of millions of Indians today. If one can’t make decisions about how resources will be used, who to have sex with, and whether or not to have babies, how can a citizen be called free?

This is why the question of “women’s freedom” needs the same answer, the same tactics. Non-cooperation. Non-violence. De-conditioning. If freedom means anything to us, we must struggle as if we struggled for India, in the name of humanity and justice.

But the truth was slightly different. For starters, there was no ‘us’. There were hundreds of kingdoms, all part of a power hierarchy. A kingdom could be ‘sovereign’ but it might have to pay tribute to a bigger, more powerful kingdom. That was the only way to stay ‘independent’. It was the only way a king or queen could stay on the throne. If kings or queens were devoted to citizen welfare, they would also sign peace treaties to save people from violence and total economic ruin in the course of war. Our ‘foreign invaders’ could be Bhutanese (from Assam’s perspective), Maratha (from Bhopal’s perspective), or Tibetan (from Spiti’s perspective).

But Britain gained in power to the extent that almost all kingdoms – despite racial and cultural differences – suffered. Taxes were heavy; wealth was leaving the subcontinent. Now, there was a common enemy, racially different and blatantly discriminatory. So enough people – even the rich – could say: ‘Quit India’.

It took a long time but Britain did quit India, politically at least. And ‘India’ was born. But that didn’t mean we stopped trying to enslave other citizens.

There was a recent news article about a domestic worker from Jharkhand, a teenaged girl, who was beaten and starved for three days by her employer. Does this not sound like a slavery? The teenager survived but imagine her situation – she doesn’t speak any of the three main languages that most neighbours would have spoken; she had no money and circumstances at home were probably desperate enough for her to be sent to Mumbai in the first place.

Another report from Kanpur. A husband asks his pregnant wife to undergo a sex-determination test for the foetus. She refuses. He pours acid on her private parts. Now think of the wife’s situation – perhaps she has no money or property; if she had walked out on her husband before, she would face the risk of attacks from other men. The police and legal system being what it is in our country, she couldn’t have hoped for timely intervention in any case. Does this not sound like a slavery-enabling system?

It has become fashionable to dismiss M.K. Gandhi and his methods of non-violence, non-cooperation, and self-reflection. But there is a reason Gandhi chose these tools in the struggle for freedom. What was being done to us by imperialist forces was violence. Indians were not necessarily being locked up in a cage, or whipped. Those might be our mental images of slavery. Our main shackles were economic and psychological.

We could not make decisions for ourselves, nor controlled natural resources. If we tried to, we confronted physical violence. Which is exactly what is happening to hundreds of millions of Indians today. If one can’t make decisions about how resources will be used, who to have sex with, and whether or not to have babies, how can a citizen be called free?

This is why the question of “women’s freedom” needs the same answer, the same tactics. Non-cooperation. Non-violence. De-conditioning. If freedom means anything to us, we must struggle as if we struggled for India, in the name of humanity and justice.

First published here

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Flushing for karma

I was slightly jealous when I read

about this Kerela initiative – 'e-toilets' at government medical

colleges. These toilets are called Eve's Own for they will reportedly

have napkin-vending machines, incinerators, automatic sensor taps,

fans and lights that auto-start when you step in. Plans include

sensitive doors that open only if the water tank has enough water.

Of course, it is a pity that these are

restricted to medical colleges. There is no reason why all public

toilets should not be woman-friendly. Even if they're coin-operated,

it would be a huge improvement from current washrooms where coins are

no guarantee against dry taps, broken door latches, flooded floors,

and worse.

Curiously enough, I have often heard it

said that “women's toilets are dirtier”. Usually it is women who

say this. Having not been in a men's toilet, I cannot compare but I

have been to offices and restaurants that have no separate male and

female toilets. I found there was very little difference in levels of

cleanliness. This must mean that women are either not that much

dirtier, or that they become more careful about toilet habits if they

know that men will be witness to these habits. Or, men are cleaning

up after women (hey, the world is full of wonders!)

Back in college, I recall discussions

where girls would swap tales of toilet adventure. I myself recalled

how my mother always carried a bedsheet when we went on outdoor

picnics. Others mentioned moms who usher kids to the edge of railway

platforms, urging them to just 'go'. One girl mentioned that she had

witnessed saree-clad women relieving themselves whilst standing

upright. This had quite an impact on our youthful imaginations –

the possibility of doing such a thing had not struck us before, but

in an emergency... Of course! One can and one should!

Over the years, I had my share of fury

and frustration. As a young reporter who was always on the move, this

was anxiety number one – how far was the nearest loo? I remember

times when I was out on assignment in residential colonies, and there

was not one public toilet in the area. I waited hours before an

option presented itself, then I'd be lucky if the door was not

locked. If there was running water, I felt positively blessed.

All Indian women are familiar with this

sort of panic, regardless of whether they are 'working' women or not.

For one, there is no guarantee that there is a toilet even in the

house. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 3), only

26 percent of rural India had access to sanitation. A Unicef report

estimates that 54 percent of India does not have access to clean,

safe toilets. Hundreds of millions live in mortal terror of – at

worst – an attack by human or animal or insect, and – at least –

the fear of infections. Things are not much better in cities where

there are no semi-discreet woods or rocks or fields, so you could

just go under the open sky.

Life is hard enough without having to

worry about how much water you can afford to drink before you step

outdoors. Many women endorse glassy air-conditioned malls just for

their promise of usable toilets.

First published here

Tuesday, August 06, 2013

Down the drain... Back again?

Did you hear about the contamination

levels of waterfronts in Mumbai? It's worse than it used to be. The

beaches are filthier. And what's more, much of the contamination is

faecal matter. Yes, shit mostly.

Before you start blaming the hundreds

of thousands of people who must squat on the beach – although there

is that problem too – consider the facts. Mumbai generates 2677 litres of sewaage, every day. Of this, only 774

million litres is treated. The rest just goes into the sea.

Perhaps you have heard of men

dying in sewers while trying to clear blockages. Sometimes, people

die just breathing the noxious air around a manhole. There was a news

report about the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation wanting to install a

ventilating system over manhole covers, after three people died from

the poisonous gases wafting up. There was another report about a

seven-year-old boy dying after he fell into an open drain in

Mehrauli, Delhi.

India has hundreds of open drains in

each city, and there are hundreds of cities. It is high time we began

to ask – how is it that we invest hundreds of billions in aircrafts, even space-craft, but are unwilling to find clean, efficient

technologies to fix the overwhelming toilet and sewage problem?

How is it that we continue to flush our

filth into rivers that form our drinking water supply? In Pradip

Saha's documentary 'Faecal Attraction', a dual question is posed to

the citizens of Delhi – where did they think their water comes

from, and where does the shit go?

Some respondents sheepishly admit

that the answer to both is probably the river Yamuna. Others,

including young and educated citizens, seem to think that once they

flush the toilet, the sewers carry their shit to a mysterious

location, a convenient 'somewhere else'. As the documentary shows,

sewage usually flows into water bodies like rivers, lakes, or else,

groundwater.

India generates 38,000 million litres

of sewage a day. 35 major cities account for over 15 million litres.

The government can treat only 12,000 million tonnes, about one-third

of the total. The Central Pollution Control Board released a report

called the ‘Status of sewage treatment in India’ a few years ago,

which said that the problem was likely to magnify to unmanageable

levels very quickly.

In one interview, Bindeshwar Pathak

(founder of Sulabh Sauchalaya) was quoted as saying that, even if we

halt the development of our cities, it would still take India 3000

years to lay safe sewer lines leading to centralised sewage

treatment plants. Only 269 towns (out of 7000) have treatment plants.

Experts suggest that a large part of the problem is that we depend

heavily on the state, and the state itself banks on a centralized

system of sewage treatment. Basically, this means that we are not

responsible for our own shit.

I can't help wondering why we don't

look to our glorious ancient culture when it comes to sanitation?

Thousands of years ago, the Indus Valley civilization had invested in

sewage systems. Humanity is as much about shitting as eating or

procreating, after all.

Nobody likes to embrace shit, of

course. But we simply can't go on if we let it flow into rivers and

seas. There are other, better ways of treating sewage. The technology

exists. And every cooperative housing society, every bunglow, every

town ought to invest in it, just as we invest in security systems and

water filters. We cannot eternally outsource the problem of sewage to

the government. We need to start seeing it as part of our own

struggle to build a decent life for ourselves.

First published here

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Starting with One

I read about two people recently who

undertook tasks that seem to require the patience and courage that's

beyond most ordinary citizens. Imagine creating a whole forest!

Imagine being an extremely vulnerable self-appointed guardian of a

forest!

That's what Hara Dei Majhi is. She

guards a wooded hill called Kapsi Dongar in Sinapalli, Odisha.

According to a magazine profile of the brave woman, Majhi took on

where her husband, Anang, left off. He had started planting trees on

a barren patch at the foothills, even at the cost of foregoing wage

labour or income through forest produce. He was too busy nurturing

and patrolling the forest. He was killed by timber smugglers in 1995.

Ever since, Majhi has been protecting

the forest herself, though in later years she also began to involve

other villagers through the Kapsi Dongar Vana Surakshya Samittee.

The second story was about a man called

Jadav Payeng from Assam. He created a forest, starting from scratch

in 1979. According to another article, Payeng had witnessed the

aftermath of flood as a teenager, and decided to do something. He

began by planting bamboo on a sandbar, brought red ants to improve

the soil, then introduced other plants. Wildlife followed naturally.

The forest is called the Mulai woods and is reportedly home to birds,

deer, rhinos, even elephants.

What both stories illustrate is that

change – public change – often begins with an individual. Nothing

ever gets done unless something shifts within one human soul.

Somebody decides to do something by becoming a person who is not

afraid to be the only person doing this, whether it is planting trees

on an island or fighting off timber smugglers.

Who wants to risk their life if there's

nothing in it for them? But that's exactly what some people do.

Others may join the campaign, driven by a sense of communal duty. Or

the awareness that everyone benefits from their efforts.

So much of our common benefits are owed

to a few people who are fighting to give us whatever little forest

cover India has. They gain little themselves, except what everyone

living in the area might gain. And yet, most of us are too

thick-headed and short-sighted to do our bit, even though it is in

our own best interests.

A recent World Bank report has said

that the cost of environmental degradation in India is about Rs 3.75

trillion a year. That would be about 5.7 percent of India’s GDP

(gross domestic product). The degradation would include not just air

pollution – though that is the most obvious contributor to the

damage – but also water and soil, as well as forest and cropland

degradation.

We pay the price with our health (not

to mention hospital bills). Still, most of us do nothing to reverse

the damage. We neither plant trees nor fight to save them. And this

ought to surprise us. An illiterate woman, armed with nothing but a

stick, can save a forest. A teenager can create a whole forest. Why

is it that our college degrees, our awareness of World Bank reports,

our relative affluence – none of it arms us with courage or

initiative?

Perhaps the difference is that Majhi

and Payeng acted as individuals, doing whatever needing doing.

Courage and passion are not mass emotions, after all. A 'system' or a

government can only reward initiative or bolster courage where it

already exists. If only there was a way of teaching ourselves how to

be more self-centered when it came to taking responsibility for

change, rather than just focussing on how much we suffer because of

nobody else will work towards this change.

First published here

Monday, July 29, 2013

On good and bad poetry

There is an art gallery called MOBA – the Museum of Bad Art – where the motto is “Art too bad to be ignored”.

I went to the website to check out the collection. I was intrigued. But a corner of my mind was also truly anxious. Anxious for the artists who find their work featured in such a gallery. It is all very well to say the work is being 'preserved' and 'celebrated' but who can stomach their work to be called 'bad'? What would it feel like to walk into such a gallery and find on the walls a shred of your own soul?

To my relief, I found that much of the work was listed as Anonymous or Artist Unknown.

I still had gooseflesh though, just thinking about the people who run this thing. They unapologetically use the phrase 'bad art' even though the curator has been quoted in Wired magazine as saying: “The paintings are all inspired, genuine attempts at something. There's a lot of passion in them, but something ran amok. As a result, they need to be seen.”

So, then, this is not 'bad' art at all. It is simply art that doesn't quite transcend the artists' limitations. It fails to be stunning. But it remains compelling (check out some of the portraiture, or the 'noods' online: http://www.museumofbadart.org/collection/ ). In fact, it is better than a lot of art I've seen in mainstream, popular art galleries. Besides, somebody is putting time and money into a 'bad art' project. Thousands of miles away, I'm staring at 'bad' paintings, trying to tap into the energy that fired the artist. I actually like a lot of what I saw.

So, what makes these paintings collectible and viewable if they're neither good nor bad? And what would be truly bad art?

Perhaps, bad art would have to be something you can ignore. It neither offends nor grabs you. It disturbs nothing, triggers nothing, causes you to wonder about nothing. Art that can, at best, be described as the sum of its materials – canvas, colour, representations of live creatures or abstract shapes. Art that does not seek to speak. Not only does it leave you cold, you suspect that even the artist did not care to submit her/his soul to the canvas.

Now, just replace 'painting' with poetry. I think, the principle holds.

It is true that I write a fair bit of bad poetry myself. I write across genres and poetry is the thing that pays least. My soul has to be hurting. My mind has to be exhausted, flying, longing to be centred and stilled. At such times, I write a poem. If I'm lucky, if I work hard and long, it turns out okay.

Occasionally, I also write for practise. Art doesn't like dabblers. Your muscles get flabby. Your eye stops 'seeing'. There's a reason for phrases like 'being out of touch' or 'losing touch'; you must keep touching what you don't want to lose. So, I make myself write sometimes even if I don't want to.

Usually, I end up discarding such poems. A stray line or two might be 'working'. I try to salvage them, using them as a diving board to work into new poems.

I destroyed much of my early work. A decade later, I could see what it was – emotional outpourings punctuated by enjambment. As if line breaks could convert a diary or blog post into art. Still, those were good practising years. Some poems escaped being awful. Some were mediocre – some metaphors, some alliteration, a few nice leaps of logic. Maybe five poems over the first five years of writing were good enough to keep in my file.

But I wanted to write better and I went looking for feedback. I joined peer review writing groups. In groups like Caferati, poetry used to dominate. There were many people writing and sharing poems. At one stage, I used to spend several hours a day reading, re-reading, carefully phrasing my critique.

Much of what we shared was bad poetry. And I don't mean 'bad' in the MOBA sense. I mean that these were poems that could easily be ignored. There was nothing to distinguish metaphors and similes. They did not disturb, trigger, cause wonder, or delight. They were a loose collection of impressions and memories.

I went to the website to check out the collection. I was intrigued. But a corner of my mind was also truly anxious. Anxious for the artists who find their work featured in such a gallery. It is all very well to say the work is being 'preserved' and 'celebrated' but who can stomach their work to be called 'bad'? What would it feel like to walk into such a gallery and find on the walls a shred of your own soul?

To my relief, I found that much of the work was listed as Anonymous or Artist Unknown.

I still had gooseflesh though, just thinking about the people who run this thing. They unapologetically use the phrase 'bad art' even though the curator has been quoted in Wired magazine as saying: “The paintings are all inspired, genuine attempts at something. There's a lot of passion in them, but something ran amok. As a result, they need to be seen.”

So, then, this is not 'bad' art at all. It is simply art that doesn't quite transcend the artists' limitations. It fails to be stunning. But it remains compelling (check out some of the portraiture, or the 'noods' online: http://www.museumofbadart.org/collection/ ). In fact, it is better than a lot of art I've seen in mainstream, popular art galleries. Besides, somebody is putting time and money into a 'bad art' project. Thousands of miles away, I'm staring at 'bad' paintings, trying to tap into the energy that fired the artist. I actually like a lot of what I saw.

So, what makes these paintings collectible and viewable if they're neither good nor bad? And what would be truly bad art?

Perhaps, bad art would have to be something you can ignore. It neither offends nor grabs you. It disturbs nothing, triggers nothing, causes you to wonder about nothing. Art that can, at best, be described as the sum of its materials – canvas, colour, representations of live creatures or abstract shapes. Art that does not seek to speak. Not only does it leave you cold, you suspect that even the artist did not care to submit her/his soul to the canvas.

Now, just replace 'painting' with poetry. I think, the principle holds.

It is true that I write a fair bit of bad poetry myself. I write across genres and poetry is the thing that pays least. My soul has to be hurting. My mind has to be exhausted, flying, longing to be centred and stilled. At such times, I write a poem. If I'm lucky, if I work hard and long, it turns out okay.

Occasionally, I also write for practise. Art doesn't like dabblers. Your muscles get flabby. Your eye stops 'seeing'. There's a reason for phrases like 'being out of touch' or 'losing touch'; you must keep touching what you don't want to lose. So, I make myself write sometimes even if I don't want to.

Usually, I end up discarding such poems. A stray line or two might be 'working'. I try to salvage them, using them as a diving board to work into new poems.

I destroyed much of my early work. A decade later, I could see what it was – emotional outpourings punctuated by enjambment. As if line breaks could convert a diary or blog post into art. Still, those were good practising years. Some poems escaped being awful. Some were mediocre – some metaphors, some alliteration, a few nice leaps of logic. Maybe five poems over the first five years of writing were good enough to keep in my file.

But I wanted to write better and I went looking for feedback. I joined peer review writing groups. In groups like Caferati, poetry used to dominate. There were many people writing and sharing poems. At one stage, I used to spend several hours a day reading, re-reading, carefully phrasing my critique.

Much of what we shared was bad poetry. And I don't mean 'bad' in the MOBA sense. I mean that these were poems that could easily be ignored. There was nothing to distinguish metaphors and similes. They did not disturb, trigger, cause wonder, or delight. They were a loose collection of impressions and memories.

Most writers simply do not read and write enough to know that you have to sweat over the lines until the page is slick with meaning. The reader does not want to witness your labours. The reader must be left with only a vague memory of salt.

The reader must be able to see a tar road on a rainy night and start thinking 'sky'. You must pull it off without saying 'sky' or 'night' and if you can help it, not even 'road'. Everyone knows the sky is full of stars. Everyone knows stars shine. Where's your 'art' if you're just going to tell me the sky was dark and the stars were shining and you were driving and the road was shining too?

Knowing this, of course, does not preclude me from the gallery of bad art. I still write bad poems. I put words on the page, trying to capture something – who knows what? Hopefully, something I didn't capture in the last poem. Hopefully, something nobody has captured before. Something that is mine to capture. Something that cannot be ignored.

The reader must be able to see a tar road on a rainy night and start thinking 'sky'. You must pull it off without saying 'sky' or 'night' and if you can help it, not even 'road'. Everyone knows the sky is full of stars. Everyone knows stars shine. Where's your 'art' if you're just going to tell me the sky was dark and the stars were shining and you were driving and the road was shining too?

Knowing this, of course, does not preclude me from the gallery of bad art. I still write bad poems. I put words on the page, trying to capture something – who knows what? Hopefully, something I didn't capture in the last poem. Hopefully, something nobody has captured before. Something that is mine to capture. Something that cannot be ignored.

This was written for Raedleaf, a site devoted to poetry.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Because the mausam is indeed awesome

Monday, July 22, 2013

Where it comes from, where it goes

The other day, I came upon a strange comment thread on a website. Somebody had posed this question: are villages an asset for India or a liability?

At first I just laughed. What kind of question was this? But then, I also read an item of news from Odisha. Apparently, a herd of elephants had wandered into Rourkela and were reportedly nudged back towards the Saranda hills. But, according to locals who live in villages on the outskirts, the herd was simply pushed out a few kilometres out of the city and the elephants were still destroying houses and crops. There were complaints that the administration seemed to care only about the lives and property of those who lived in the main city.

Could it be that somewhere in the collective city-dwelling urban subconscious, we are actually convinced that villages don't matter? Could we actually be that clueless about our own lives and our economy?

Grain and most vegetable and fruit comes from villages. Much of our diary produce and meat too. Our homes are built of cement and steel, or stone and wood – all of which are mined or made in rural or semi-rural areas. Our clothes – the good ones, anyway – are made of cotton or wool, for which we depend on farmers and shepherds. Much of the cheap labour that builds cities and provides essential services is drawn from villages.

At first I just laughed. What kind of question was this? But then, I also read an item of news from Odisha. Apparently, a herd of elephants had wandered into Rourkela and were reportedly nudged back towards the Saranda hills. But, according to locals who live in villages on the outskirts, the herd was simply pushed out a few kilometres out of the city and the elephants were still destroying houses and crops. There were complaints that the administration seemed to care only about the lives and property of those who lived in the main city.

Could it be that somewhere in the collective city-dwelling urban subconscious, we are actually convinced that villages don't matter? Could we actually be that clueless about our own lives and our economy?

Grain and most vegetable and fruit comes from villages. Much of our diary produce and meat too. Our homes are built of cement and steel, or stone and wood – all of which are mined or made in rural or semi-rural areas. Our clothes – the good ones, anyway – are made of cotton or wool, for which we depend on farmers and shepherds. Much of the cheap labour that builds cities and provides essential services is drawn from villages.

One could go on. Water, coal, herbs, medicinal extracts, and ultimately, power.

And what do we send to the villages? Manufactured goods, of course. From shampoo to tyres. Modern medicine, perhaps – if one can get a doctor to live in a village. Technology, perhaps. But the side-effects of industrial activity and modern urban lifestyles are also imposed upon villages.

Recently, matters reached a head in Kottayam district. For years, Kottayam town had been dumping its waste on the outskirts. The residents of Vijayapuram village were demanding an end to this system because they had to tolerate tonnes of garbage in the vicinity, and the dump was a breeding ground for diseases. Besides, the water in their wells was getting contaminated. When the municipality failed to listen, a rally was organized. People went to the dumping yard and forcibly locked it up.

In this instance, the protest got some media attention because the result was immediately felt in the city – garbage began to pile up in Kottayam. But there are thousands of villages affected by urban waste, industrial effluents, or because a disproportionate share of resources is taken away with no resultant benefit to the locals.

For instance, Sundargarh district in Odisha. The people who live near the mines are complaining that they don't have enough water for farms and that water is taken away to a factory several miles away. In Goa, villagers in Pissurlem were reportedly complaining about industrial waste being dumped in open spaces.

How many of us who live in cities know what happens to our waste – where does it go?

And what do we send to the villages? Manufactured goods, of course. From shampoo to tyres. Modern medicine, perhaps – if one can get a doctor to live in a village. Technology, perhaps. But the side-effects of industrial activity and modern urban lifestyles are also imposed upon villages.

Recently, matters reached a head in Kottayam district. For years, Kottayam town had been dumping its waste on the outskirts. The residents of Vijayapuram village were demanding an end to this system because they had to tolerate tonnes of garbage in the vicinity, and the dump was a breeding ground for diseases. Besides, the water in their wells was getting contaminated. When the municipality failed to listen, a rally was organized. People went to the dumping yard and forcibly locked it up.

In this instance, the protest got some media attention because the result was immediately felt in the city – garbage began to pile up in Kottayam. But there are thousands of villages affected by urban waste, industrial effluents, or because a disproportionate share of resources is taken away with no resultant benefit to the locals.

For instance, Sundargarh district in Odisha. The people who live near the mines are complaining that they don't have enough water for farms and that water is taken away to a factory several miles away. In Goa, villagers in Pissurlem were reportedly complaining about industrial waste being dumped in open spaces.

How many of us who live in cities know what happens to our waste – where does it go?

The garbage collector takes it, and that's that. We don't want to know if there is a system that ensures nobody else is made miserable or sick on our account. We don't even want to know if we ourselves are getting sick because of bad waste disposal practices, and whether there are alternatives.

Sometimes, I wonder how citizens and administrations would react if villagers began to drive up to cities with tractors piled high with personal, agricultural and industrial filth, and dumping them in any open space they saw? What do you think might happen?

Sometimes, I wonder how citizens and administrations would react if villagers began to drive up to cities with tractors piled high with personal, agricultural and industrial filth, and dumping them in any open space they saw? What do you think might happen?

Saturday, July 20, 2013

In other words, mera gaon mera des

Did you hear the news from Amsterdam about 'scum villages'. Apparently, there are 13,000 complaints of anti-social behaviour every year and now now there's a plan to create separate camps where people who are making a nuisance of themselves, or behaving in ways deemed 'anti-social' can be sent away. Families might live in caravans or be granted very basic housing while being monitored by the police.

The question is – who decides who is a nuisance to whom? There is much scope for injustice and the targetting of individuals who represent a moral/political minority, and it is a pity that Amsterdam is considering going down this slippery road. Reports say that municipal officials could identify offenders deserving of a “compulsory six month course”. Which sounds a lot like 're-education' and reminds me of non-democratic states and penal colonies.

There's a fine line between being anti-social or not wanting to follow every law in the land, and actually harassing others who might be forced out of their own homes, since they ae unable to confront or retaliate in equal measure. What makes the situation more dangerous is the politicians' attitude. One leader has been quoted as saying: “Put all the trash together”.

To think of, or describe, citizens as trash or scum is not healthy. It damages the human spirit. Which is why this whole business of 'camps' for the anti-social makes me uncomfortable.

And yet, in another corner of my head, there is also this fantasy – what if all the 'misfits' could petition the government to be allowed to set up their own villages? A bit of land where they could live by their own rules, without police interference?

We all want to pack off people we don't like to some place where they can live with their own sort. That's what ghettos are. But what if India was divided on the basis on behavioural preferences rather than linguistic or religious heritage? The only law that would apply to all would be against physical assault, murder and enslavement. At 16, children could decide whether they wanted to stay put with their parents, or start traveling to look for a colony where they share the values of the local residents.

There was an online test doing the rounds a while ago. It figured out where you 'belong' based on your values and personal politics. It turned out that many of the people I like and love 'belong' in Sweden or Norway. These are tolerant, liberal, non-violent people who believe in social justice, gender equality, freedom. Yet, none of us is trying to quit India.

Perhaps we all dream of a place in India – a village or town – where we could apply for domicile on the basis of our personal values. For instance, a colony of atheist artists who cultivate land – what would it be like? And why not have a colony of misogynists where all misogynists can live happily ever after?

If only the government could do a nation-wide psychological survey to figure out who wants a zero tolerance approach to sexual violence? Who prefers a soft apologists' approach? Who wants the freedom to harass man, woman, child or animal with no serious consequences?

I can imagine such a survey: “Whoever believes in dowry, stand in this line. Whoever believes in purdah, stand in that line. Who does not believe in legal marriage or inheritance? Raise your hand.”

If only we could all find our nearest soul-citizens, and then go off into our own scummy villages where our own rules apply... That would be something, eh?

The question is – who decides who is a nuisance to whom? There is much scope for injustice and the targetting of individuals who represent a moral/political minority, and it is a pity that Amsterdam is considering going down this slippery road. Reports say that municipal officials could identify offenders deserving of a “compulsory six month course”. Which sounds a lot like 're-education' and reminds me of non-democratic states and penal colonies.

There's a fine line between being anti-social or not wanting to follow every law in the land, and actually harassing others who might be forced out of their own homes, since they ae unable to confront or retaliate in equal measure. What makes the situation more dangerous is the politicians' attitude. One leader has been quoted as saying: “Put all the trash together”.

To think of, or describe, citizens as trash or scum is not healthy. It damages the human spirit. Which is why this whole business of 'camps' for the anti-social makes me uncomfortable.

And yet, in another corner of my head, there is also this fantasy – what if all the 'misfits' could petition the government to be allowed to set up their own villages? A bit of land where they could live by their own rules, without police interference?

We all want to pack off people we don't like to some place where they can live with their own sort. That's what ghettos are. But what if India was divided on the basis on behavioural preferences rather than linguistic or religious heritage? The only law that would apply to all would be against physical assault, murder and enslavement. At 16, children could decide whether they wanted to stay put with their parents, or start traveling to look for a colony where they share the values of the local residents.

There was an online test doing the rounds a while ago. It figured out where you 'belong' based on your values and personal politics. It turned out that many of the people I like and love 'belong' in Sweden or Norway. These are tolerant, liberal, non-violent people who believe in social justice, gender equality, freedom. Yet, none of us is trying to quit India.

Perhaps we all dream of a place in India – a village or town – where we could apply for domicile on the basis of our personal values. For instance, a colony of atheist artists who cultivate land – what would it be like? And why not have a colony of misogynists where all misogynists can live happily ever after?

If only the government could do a nation-wide psychological survey to figure out who wants a zero tolerance approach to sexual violence? Who prefers a soft apologists' approach? Who wants the freedom to harass man, woman, child or animal with no serious consequences?

I can imagine such a survey: “Whoever believes in dowry, stand in this line. Whoever believes in purdah, stand in that line. Who does not believe in legal marriage or inheritance? Raise your hand.”

If only we could all find our nearest soul-citizens, and then go off into our own scummy villages where our own rules apply... That would be something, eh?

First published here

Monday, July 08, 2013

Tech it up

Recently, I had to apply for a new PAN card. It was a relatively painless process, despite a few weeks' delay on account of a misplaced cheque. But what made me feel better through the whole business of following up on the application was that there was someone I could reach. The fact that I could send and email and actually get a response, that I could call a helpline to understand the problem and an executive told me what to do – this made me feel less frustration. And when the application was processed, I was sent an update via email, telling me that the card had been dispatched and would reach me soon.

Interactions with the state have become slightly smoother because of newer technologies. You don't have to waste precious time standing in queues, watching the defensive faces of government employees who are responsible for either blocking or expediting your file. Now citizens can apply online for a few basic services and receive updates on mobile phones or via email.

This is a major relief, of course. Many communication problems can be resolved if the technologies push deeper into the countryside, and are made available in more languages. But the first step is for the government to decide to use technology to make life better, simpler, more fair for citizens.

Even with existing knowledge, much can be done to improve the average citizen's relationship with the state. CCTV cameras are constantly being used to check crime. Video-calling and conferencing is connecting families across the globe. There is no reason these should not be used to monitor village schools and hospitals, so teachers and doctors cannot absent themselves so easily.

In fact, the failure to enable things like tracking files online through government departments is making us more vulnerable to corruption. We should be able to see why municipal clearances for various projects are granted or denied. We should be able to report violations of the illegal use of public space to the concerned state department.

Citizens should be able to reach the administration without wasting time and money travelling to block offices. Even if they're illiterate, or don't have personal laptops or uninterrupted power supply, it is possible to enable a video-call using a combination of solar energy, a public media centre and the internet. They should be able to make a phone call to complain if their pension are delayed.

Last week, I'd mentioned a protest in Delhi, where activists demanded solar energy. They wanted to emphasize that many alternatives are available to the human race to generate electricity, and reports said that they had connected their bicycles to a sign that was lit up as the activists pedaled.

Indeed, there are a dozen possibilities. In Tambaram municipality, methane gas was drawn from sewage and used as cooking gas for local residents. A bio-methanation plant has reportedly been set up to treat sewage generated from public toilets, which serves the dual purpose of ensuring sanitation and reducing the use of kerosene or LPG in kitchens. The state of Chhattisgarh is reportedly trying to use satellite imagery to curb illegal mining and transport of minerals.

In other nations, gyms have used exercise equipment to generate electricity. Magazine reports have mentioned music festivals that experimented with bicycle-powered concerts, and bars that make customers pedal up the energy needed to create their cocktails.

If we'd snap out of our overwhelming dependence on huge grids powered by coal or hydro-power, every district would have a shot at energy independence, we'd use natural resources better, and we'd all be one step closer to de-centralized democracy.

Interactions with the state have become slightly smoother because of newer technologies. You don't have to waste precious time standing in queues, watching the defensive faces of government employees who are responsible for either blocking or expediting your file. Now citizens can apply online for a few basic services and receive updates on mobile phones or via email.

This is a major relief, of course. Many communication problems can be resolved if the technologies push deeper into the countryside, and are made available in more languages. But the first step is for the government to decide to use technology to make life better, simpler, more fair for citizens.

Even with existing knowledge, much can be done to improve the average citizen's relationship with the state. CCTV cameras are constantly being used to check crime. Video-calling and conferencing is connecting families across the globe. There is no reason these should not be used to monitor village schools and hospitals, so teachers and doctors cannot absent themselves so easily.

In fact, the failure to enable things like tracking files online through government departments is making us more vulnerable to corruption. We should be able to see why municipal clearances for various projects are granted or denied. We should be able to report violations of the illegal use of public space to the concerned state department.

Citizens should be able to reach the administration without wasting time and money travelling to block offices. Even if they're illiterate, or don't have personal laptops or uninterrupted power supply, it is possible to enable a video-call using a combination of solar energy, a public media centre and the internet. They should be able to make a phone call to complain if their pension are delayed.

Last week, I'd mentioned a protest in Delhi, where activists demanded solar energy. They wanted to emphasize that many alternatives are available to the human race to generate electricity, and reports said that they had connected their bicycles to a sign that was lit up as the activists pedaled.

Indeed, there are a dozen possibilities. In Tambaram municipality, methane gas was drawn from sewage and used as cooking gas for local residents. A bio-methanation plant has reportedly been set up to treat sewage generated from public toilets, which serves the dual purpose of ensuring sanitation and reducing the use of kerosene or LPG in kitchens. The state of Chhattisgarh is reportedly trying to use satellite imagery to curb illegal mining and transport of minerals.

In other nations, gyms have used exercise equipment to generate electricity. Magazine reports have mentioned music festivals that experimented with bicycle-powered concerts, and bars that make customers pedal up the energy needed to create their cocktails.

If we'd snap out of our overwhelming dependence on huge grids powered by coal or hydro-power, every district would have a shot at energy independence, we'd use natural resources better, and we'd all be one step closer to de-centralized democracy.

First published here

Sunday, July 07, 2013

Un- comical adventures

My second graphic story for Mint's 'The Small Picture' had appeared a few weeks ago. This one is about the trials and heartbreaks of home-seekers, particularly single people, in Mumbai.

Here's a link: http://www.livemint.com/rw/LiveMint/Period1/2013/06/20/Photos/StandingObjects/Jun21_tsp.jpg

Here's a link: http://www.livemint.com/rw/LiveMint/Period1/2013/06/20/Photos/StandingObjects/Jun21_tsp.jpg

Friday, July 05, 2013

3 new poems in Big Bridge

I have three poems in the new anthology of Indian poetry at Big Bridge:

'Cine Sestina'

'City, Twilight'

'Lifer Giving Advice to New Convict in Female Ward'.